Kondo the Barbarian: Decluttering the Human Herd (When Joy Becomes the Standard, Death Becomes the Service)

Nature, bless her manic little heart, has always been a hoarder.

She can’t help herself. Fish lay ten thousand eggs just to produce one self-actualized salmon. Trees fling acorns like drunks tossing Mardi Gras beads, hoping one might take root before a lawn crew mulches it. And human beings? Nature’s grains of sand—bound to chafe your crotch and jam the gears.

Isak Dinesen, that sly observer of life’s unnecessary splendor, once noted that nature doesn’t just produce more eggs than will ever become fish—she creates more simulated humans than real ones.

Think about that.

Trial-run people. Beta-test souls. Placeholder citizens just sophisticated enough to tweet and twerk, but not quite enough to evolve.

Where Dinesen saw a tragic and holy excess—life in its rough draft, teeming and gloriously inefficient—our modern custodians see something else entirely: clutter. Biological overstock. Inventory glut. A goddamn mess.

And mess, my dear beloved reader, is no longer permitted.

We are now a civilization obsessed with curation, with paring things down to their most joy-sparking essence.

My dad once got his hands on an original Charles Schulz comic strip.

Three panels. Lucy screaming “Blockhead!” at an off-panel Charlie Brown.

Linus, child philosopher and part-time narc, replies:

“You shouldn’t call him that.”

“Why not?”

“What if he really is a blockhead?”

The strip was drawn horizontal.

But my dad only had a vertical frame.

So he did what any father armed with a hacksaw and a questionable aesthetic instinct would do—

He chopped the thing into thirds and stacked it like a totem pole of cartoon neurosis.

Lucy at the top, shrieking into the void.

Linus in the middle, contemplating moral relativism.

Charlie Brown? Erased. Cropped out of his own comic strip.

And that—right there—is where we live now.

We no longer ask what anything means.

We ask if it fits the goddamn frame.

If it compliments the palette. If it offends the algorithm.

If it sparks joy—or just sparks static.

Enter Marie Kondo: the soft-spoken harbinger of the controlled burn.

With the expression of a cult recruiter and the emotional range of beige, she asked the question heard round the world:

“Does it spark joy?”

And just like that, people began purging their lives of complexity.

Books, memories, relatives, dissent—gone.

Cluttered? Canceled.

Dissonant? Deleted.

It was sold as lifestyle advice.

It metastasized into policy.

This is how globalism sells sterilization—not with blood, but with branding.

Not with gulags, but with user experience.

You’re not being rounded up. You’re being gently de-platformed.

No boots. Just smooth jazz and a Terms of Service.

Joy became the metric.

Compliance became the aesthetic.

And now the entire world is being curated by a cartel of sentiment managers.

They call it simplification.

But what they really want is subtraction.

You don’t fit the frame?

Out you go.

Too loud? Too complicated? Too historically inconvenient?

Snip snip.

We’ve turned into decorators of the human soul.

Trimming, filtering, erasing.

One blockhead at a time.

You can see this philosophy gleaming in the polished sterility of Canada’s MAiD program: Medical Assistance in Dying.

It sounds like a customer service feature. Like something you’d find buried in the Help menu of a gently used iPad.

But it’s real. And it’s growing.

In 2016, just over 1,000 Canadians used it. In 2023, over 13,000. In Quebec, it accounts for more than 10% of all deaths. That’s not a mercy—it’s a market share.

And people aren’t just dying because they’re terminally ill. They’re dying because they can’t pay rent. Because they’re depressed. Because they were put on hold by the healthcare system so long they figured they might as well cancel the subscription entirely.

There’s a woman in Ontario seeking assisted suicide due to long COVID and eviction. A veteran with PTSD was offered death instead of treatment. Another efficiency, another checkbox cleared.

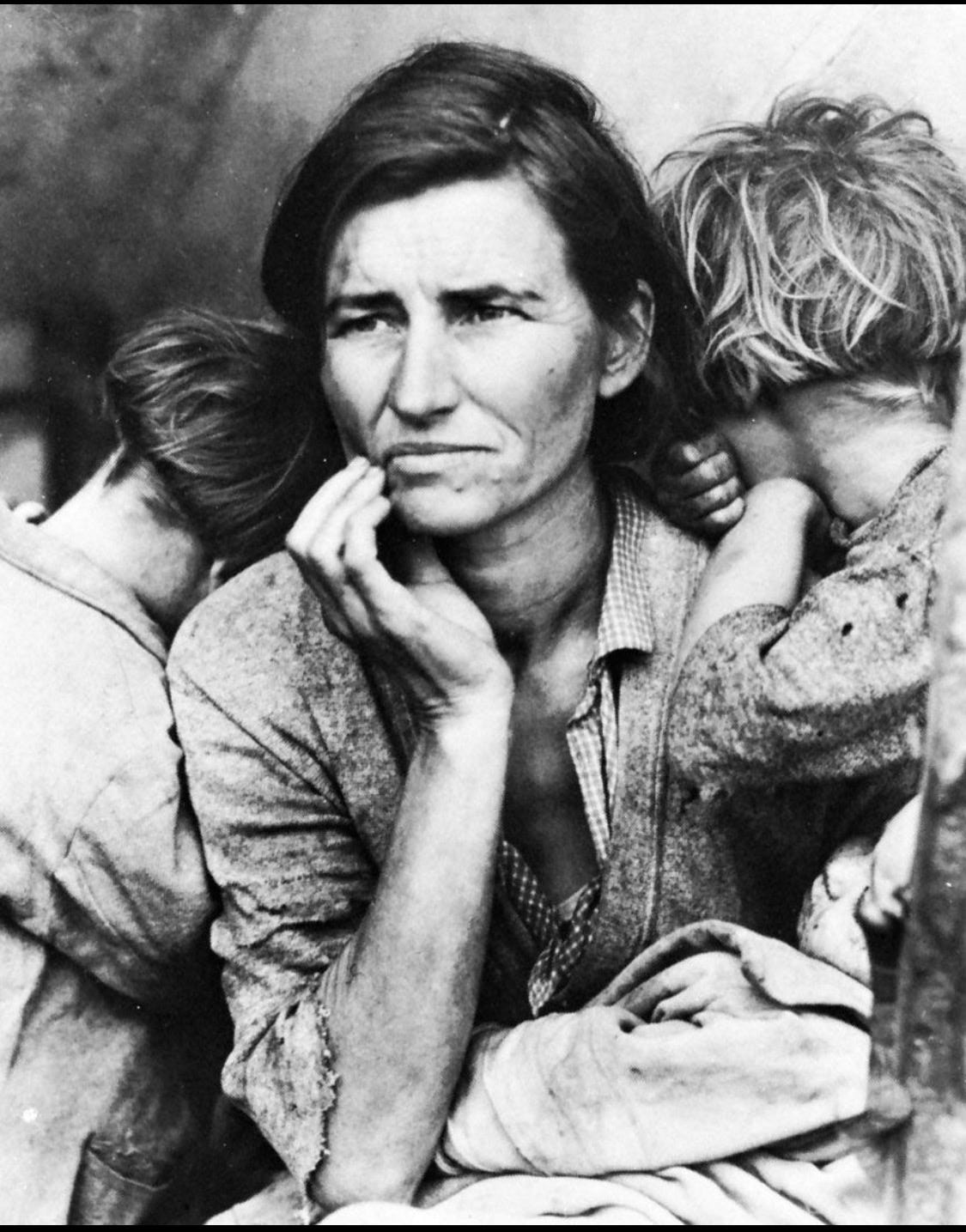

Dorothea Lange, Migrant Mother, 1936. She endured what our systems would now call “clutter.” She sparked no joy—only unyielding strength.

We’re not killing people. We’re “empowering” them.

The state doesn’t say, “You must die.” It says, “You may—and here’s the form, a chamomile tea, and a licensed therapist to confirm you still mean it on the way out.”

And it’s here we must pause—just long enough to admit there are, on occasion, moments when choosing death is a lucid and sacred kind of autonomy.

Think of Whose Life Is It Anyway?—the 1981 film adaptation of Brian Clark’s play.

A sculptor, paralyzed from the neck down, petitions for the right to end his life. Not because he’s poor or neglected, but because the core of what made him him—his ability to shape form, to create—had been irreversibly severed in a single, catastrophic moment. No one cornered him. No one penciled in his death between billing cycles. No clipboard came with a scented pen.

He made a clear and personal claim: that life, for him, had become a cell.

That argument has gravity. It demands respect.

But what we’re seeing now? This isn’t that.

This is something colder. Quieter. Ubiquitous.

We’re not protecting the right to die—we’re massaging the desire to.

We’ve built a pipeline that starts with despair and ends in soft-lit elimination, with just enough velvet rope to make it feel like a VIP experience.

That isn’t compassion.

It’s cost containment.

It’s decluttering, with a consent form and a federally-funded ride home for your ashes.

And make no mistake—this isn’t just the byproduct of public fatigue or economic strain. It’s philosophical. Global. Intentional.

Somewhere in the cold heart of technocratic consensus, the question has already been asked: Does humanity spark joy?

And for those seated at the long tables in climate-controlled rooms, the answer—at least for the masses, the messy, the redundant—appears to be a quiet, calculated no.

Not with malice. Not even with much emotion. Just the sterile dispassion of the curator who decides that certain exhibits have run their course. And from that decision flows policy, programming, persuasion. Not extermination—elimination by encouragement. Not genocide—joyless omission.

Because when joy becomes the bar for continued existence, you’d better be charming, debt-free, and emotionally gluten-free.

If you’re too broken, too complicated, too… unoptimized?

Then maybe it’s time to fold yourself into thirds and slide neatly into the recycling bin of modernity.

We’ve replaced moral absolutes with UX design.

Where Kant saw inherent dignity, we now see user fatigue.

You’re either frictionless or disposable.

Hannah Arendt warned us: the greatest evils are carried out not by monsters, but by the ordinary, the procedural, the obedient.

And now we’ve procedurized disappearance.

We’ve branded offboarding.

We’ve built an elegant, compassionate exit for the inconvenient.

This is what happens when a culture loses its tolerance for mess—for persistence, for suffering, for the unsightly labor of care.

We no longer carry one another’s burdens. We audit them.

And if they don’t spark joy?

Well, we thank them, bless them, and call the appropriate service line.

The old eugenicists were loud.

The new ones are curated.

The old ones used uniforms.

The new ones use soft skills and trauma-informed checklists.

And don’t you dare think this stops at Canada. The UK’s already hovering over the “Accept All Cookies” button. Belgium is euthanizing depressed teenagers. The Netherlands will do it for children under twelve if the parents and ethics committee both wink at the same time. Silicon Valley will monetize the app version soon enough. It’ll sync with your Apple Health data and play Coldplay during the fade-out.

We’ve built the first death cult in history with a customer service department.

And it all began with a simple question: Does it spark joy?

Dinesen understood that most of what matters doesn’t.

Suffering doesn’t. Doubt doesn’t. Love—real love—often doesn’t.

But we don’t have time for that anymore. Not in this economy. Not in this app cycle. Not in this freshly mopped, noise-canceling culture of therapeutic deletion.

And so we tidy. We optimize. We purge.

Not out of hate—but because it’s cleaner.

Because some lives don’t fold neatly.

So here we are. Standing at the edge of the sterile womb of progress, lit by LEDs and sponsored by the soft silence of polite off-ramps.

The herd is being thinned—efficiently, elegantly, and above all, kindly.

We thank you for your service.

We wish you peace.

And if nothing else, we hope your absence finally sparks joy.

But don’t comfort yourself thinking this is about someone else.

It never is.

The question—Does this life spark joy?—was never reserved for the terminal, the broken, or the burdensome.

It’s already being asked—of all of us.

Of the slow. The stubborn. The imperfectly wired.

Of those who cost too much to fix, or take too long to cure.

Of your aging parents. Of your child with too many questions.

Of you, on a day you no longer sparkle.

This isn’t mercy. It’s metrics.

This isn’t choice. It’s choreography.

The new exterminators don’t march.

They hold degrees in bioethics and speak in passive verbs.

They draft policies in natural light, using fonts that make you feel safe.

And they’ve already decided.

You are too many.

Too fragile.

Too much.

You won’t be dragged.

You’ll be guided.

Applauded for your maturity.

Assured that this, too, is a form of love.

And when the signature is dry and the room is quiet—no one will call it what it was.

Just one less burden.

One less cry in the hallway.

One more square foot of clean, untroubled space.

They will say you chose it.

They will say you thanked them.

And in some small, forgotten folder, the world will mark itself lighter.

(Please subscribe. Please open what I send you, even if you shit-can it immediately thereafter. Algorithms, you know)

A profoundly moving read, Dean, thank you. Before you even mentioned Hannah Arendt, as I read, "the banality of evil" was loud in my head. Over decades, I've watched the death culture take hold with horror. My involvement in the Right to Life movement began in the early '70s and never allowed the increments of the encroaching nightmare to escape my notice. The oblivion of so many adds to the horror.

I'll admit Dean, your thoughts on this made me pause, and consider. After watching a recent interview on YouTube with Jimmy Dore with Jame's Corbett explaining that all Globalist are Satanic Eugenicist, and we look around at neighbors who are bubble-wrapped in their 'me, myself and I' world, telling us about somebody named who that cares. One is left to ponder why the premature death of an individual is called a tragedy, but if lumped into that collective number of a million, they are only a statistic. When life beats us up one side and down the other, it is difficult not to get depressed sometimes and those who have had to endure the trial by denial and put on happy faces rarely are able to keep up appearances when having to make the hard choices that they would rather avoid. There are connections that don't require the internet, and networks that are beyond human comprehension. It's something like watching an episode of "Little House on the Prairie" When a gentleman from the city is trying to explain to Little Laura Ingle's about how his book told him what bait to use to fish with. She politely responded "Maybe the fish haven't read the book".

I cannot presume to speak for others, but for myself, my own day of reckoning was the realization that every life is precious until is is mediated, curated and polluted with bad ideologies. So how do whole populations become so bewitched that they no longer see that fundamental rights are supposed to be a shared value? In my never ending quest for answers, sometimes I come upon some gems of individuals who did their own research like Dr. Karen Mitchel in the YouTube video of: "The Hidden Dangers of High-Functioning Predators w/ Dr. Karen Mitchell"

Here is the link for your review and consideration, but we do see evil in high places.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nO8hzhLKsKE